Ghana's Hidden Need for Affordable Housing

by Rick Juliusson

"Where's the poverty housing?" That was my first reaction as I arrived at the district capital town Agona, Ghana, where I had been assigned as an International Partner. The big houses with tin roofs, plastered walls, cement floors and electrical wires defied my definition of poverty housing in rural Africa -- generally small huts with mud walls, a grass thatch roof and dirt floor.

As a start, the local Habitat chairman and I conducted a survey to identify the town's housing needs. We surveyed 17 applicant families to get details of their living conditions and to ask them, "What are the three greatest problems a Habitat house will solve?"

The first sobering lesson we learned was that they didn't have toilets. No facility whatsoever. The applicants walked almost a kilometer and a half to public toilets where they paid a fee to use them. Beyond the obvious inconvenience and lack of privacy, the public facilities are dirty, overused and breeding grounds for mosquitoes -- a huge health problem in Ghana. Like most of the surveyed families, Samwel Kwakye identified private bathroom facilities as among the greatest benefits of new housing.

If the lack of bathroom facilities surprised me, another common survey response floored me. Almost all the surveyed families noted that the Habitat houses were "a bit spacious." They were talking about a 12-foot-by-23-foot house: two 11-foot-by-11-foot rooms, and a utility block with a shower, a toilet and a 5-foot-by-8-foot kitchen. "How could this be spacious?" I thought.

While appearing large, the houses I had seen when I first arrived were actually compounds, housing many families. Usually an entire family shares an 11-foot-by-12-foot room. Along one wall, hidden behind a curtain, are the parents' bed and most of their possessions. A few chairs, maybe a table with a TV or radio and more possessions are pushed aside each night to make floor space for the children to sleep.

This single-room family life is not the exception, but the norm. I had hoped I was seeing the worst cases, but everyone lives like this -- families of government workers, teachers, farmers, nurses. All of them sleep, cry, entertain and live together in one room.

Of course, not everyone is so lucky to share this single room with their spouse and children. Samwel Amofa, a 33-year-old auto mechanic, shares a room with his 36-year-old brother. His wife and five children live in her parents' house across town. "I can't bring my family to live in this," he says. "I'll be happy to own my own house so I can live with my wife and children permanently."

Amofa has it better than Sadil Hussein, an administrative officer with the government's District Commission. His wife and seven children live in northern Ghana, a 15-hour bus ride away. The family lives in a compound house in which several families occupy one room of a rectangular structure built around a central dirt courtyard, with three or four rooms on each side of the rectangle.

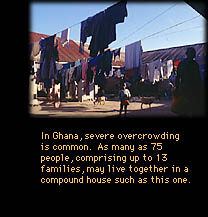

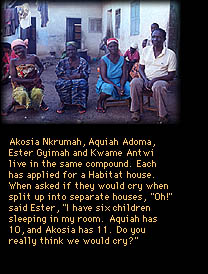

As many as 75 people comprising as many as 13 families may live in one of these compound houses. In one compound house, three unrelated families are waiting for -- or rather working for -- a Habitat house. Samwel Osei Manu occupies one room with his wife and four children. He and the 12 other families in the house all share one shower, with walls 5 feet high, two open-air cooking huts and a central courtyard crisscrossed with lines of laundry. No wonder that he, like most families, listed a lack of "secrecy" as one of his top three problems.

"Everybody knows what I eat, who my guests are or if I'm out of money," Manu explained. Quite literally, people can see his dirty laundry.

These tight living conditions inevitably lead to fighting. On visits to prospective Habitat homeowners, I was shocked by how often I witnessed loud, long, fierce arguments. Ghanaians are an exceptionally friendly, peaceful and hospitable people, and yet 11 out of the 17 families surveyed mentioned fighting as a major problem. Manu referred to it as "fighting among inmates."

One common cause of fighting is food. Ghanaian culture requires you to offer food to anyone passing by and to oblige any requests for food. The economics of this custom, especially if not reciprocated by certain house dwellers, are a major burden in a 10-family compound.

"When I get my Habitat house," Yeboah stated simply, "I'll be able to eat my own food!"

All of these conditions create a major health hazard: preparing and eating food in muddy, open courtyards, sleeping together in poorly ventilated rooms, stress from fighting and lack of privacy, sleeplessness due to noise and overcrowding. It's easy to see the toll on parents trying to pay the medical bills and put in a good day's work or on children trying to perform well in school.

Nevertheless, many surveyed listed ownership as chief among the reasons for wanting a Habitat house -- and they share that with Habitat families worldwide.

"Happiness from owning my own house," says Amoaka Mensa.

"Self-dependence," lists Samuel Amofah.

"Getting a house for our children," dreams Thomas Gyebi.

What did this survey show me? A set of housing problems I had never imagined: single-room families; separated families; no private toilets or showers; overcrowded houses with resultant stress, lack of privacy, conflict and health issues. To label the conditions inadequate doesn't capture the true loss of dignity, hope and security.

But for all the different reasons for the people of Agona to join Habitat, the dream remains the same: the peace of mind from homeownership. With eight houses currently under construction at the new affiliate -- entirely from locally raised funds -- I pray that Habitat helps some of these dreams to come true. In the meantime, I am encouraged by Kwame Antwi's optimistic appraisal of the situation: "We have no problems, only poverty."

For additional information, please visit the

Habitat for Humanity International web site

Who

Who